Glengarry and bonnet badge of the

Highland Light Infantry of Canada

Shoulder title of the

Highland Light Infantry of Canada

The Mackenzie Tartan of the

Highland Light Infantry of Canada

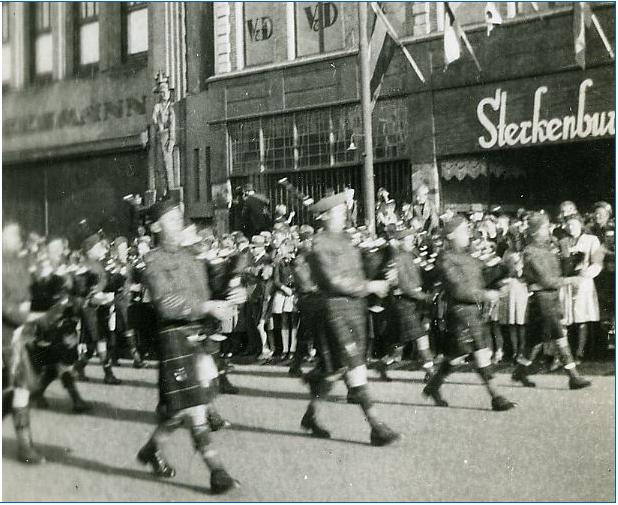

(See above) On

photographs of the

Highland Light Infantry

of Canada's Pipe band three different types of sporran can be

distinguished:

(From Left to Right) 2 black-tasseled White hair Sporran for the

Pipers, 5 white-tasseled Black hair Sporran for the Pipe Major,

and 3 white-tasseled Black hair sporran for the Pipe Sergeant.

This is the Regimental History

Book of

the 1st. Battalion of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada,

from which quotes will be used below here, on this page,

with additions from "Proud Heritage, Vol4", the Regimental

history of the Sister regiment:

The "Imperial" Highland Light Infantry from Scotland

(See Illustration below)

(Above)

"Proud Heritage, Vol4", the Regimental history of the Sister

regiment:

The "Imperial" Highland Light Infantry from Scotland

The Highland Light Infantry

of Canada was allied to the Highland light Infantry (City of

Glasgow Regiment) of Scotland. They were initially kitted with

green glengarries, Mackenzie trews and a scarlet doublet, but

became kilted in 1935. Pipers and bandsmen in full dress wore a

feather bonnet with red hackle, Mackenzie hose tops for the pipers and red and

white for the regiment, and a blue balmoral bonnet with a diced

border, green tourie and a red and white hackle.

Source:

https://es-la.facebook.com/RHFCPD/photos/a.906156826093585/4305875302788370/?type=3&theater

H.L.I. of Canada Pipers and Drummers at Cove Field, Quebec City,

1941.

Left to Right: Bill Bowden A. L. Harris C.

Cole "Ducky Mollard" K. Mc.Lean Bill Smith A. Presswell

H.L.I. of Canada Pipes and Drums at Camp Debert (N.S), 1941.

Back:

W. Smith A. Presswell L. Livingstone D. Mc.

Cutcheon C. Walpole

Front: S. Corstorphine (P.M) A.L. Harris

K. Mc.Lean W. Melville

The following is quoted from the

aforementioned sources:

Defence not Defiance

Waterloo Region, Ontario, Canada, 1941

"Not in Canada in those early days was there need for

recruiting parades and posters, the blood stirring music of

bands, or frenetic speeches to rouse a false patriotism. The

word went out... 'the H.L.I. is mobilizing'... and the response

to the word was so overwhelming that mobilization was completed

quietly, efficiently, and with record-making speed... It was

mobilization of a citizen army, of men and youths who flocked to

the Colours, not with any false idea about the glamour of war,

but with a true ideal as their spur. They mobilized for defence,

not defiance. "

Many were already in the militia before The Regiment was ordered

to mobilize in May of 1940, while others flocked to the

recruiting drive afterwards, coming from such nearby communities

as Preston, Hespeler, Ayr and Breslau.

Although the city of Kitchener had its own militia regiment, The

Scots Fusiliers, they were yet to receive mobilization orders

from Ottawa, which meant that a flood of militiamen from the

Scots Fusiliers were requesting transfers to the nearby Highland

Light Infantry in Galt. This was no problem for the H.L.I.'s

recruiting office; their orders were to recruit enough to fill a

standard Canadian Active Service Force (C.A.S.F.) Battalion of no

less than 800 soldiers.

Once they had recruited over 1,000 volunteers, The First

Battalion of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada shipped out

to Stratford for basic training.

Shake out, then ship out

It was not until January P, 1941 that the First

Battalion shipped out of the province to join the gathering of

fledgling military personnel, as they moved off by train first

to Quebec City then Debert Camp, Nova Scotia. It was there they

became part of the new 3rd. Division, which was made up of nine

battalions exactly like them. For five months they soldiered,

then were given a final leave of three weeks before leaving for

Great Britain. By train the men of Waterloo County arrived back

home so that families and loved ones could be together. Sadly,

for many it would be the last time.

Troopship S.S. Strathmore

Troopship S.S. Strathmore

Gross Registered Tonnage - 23,428 tons

Length x Width - 665 feet x 82 feet

Builder and Year of Build - Vickers-Armstrongs of Barrow - 1935

First Class + Tourist Accommodation - 445 + 665 persons : Total

1,110 passengers

The Strathmore was

requisitioned for use as a troopship, as were all the 'Straths'

. She saw service in most theatres of war in a rather similar

manner to the Strathnaver and Strathaird. One of her many

voyages found her in March 1941 a member of a vast convoy to the

Middle East. There were 23 troopships in all, including all the

five 'Straths', the Viceroy of India, four orient liners and

ships of the Royal Mail, Cunard,Union castle, CPR together with

Dutch and French Liners. P & O were thus well presented.

Gourock, Scotland July 1941

As the S.S. Strathmore came into sight of Scotland,

soldiers filled the decks to watch the land slowly loom closer.

After a monotonous trip across the Atlantic, everyone was

anxious to touch solid ground, especially those who didn't

handle the churning of the ocean well. The port of Gourock had

always been a busy place for ocean going vessels. Since the war,

though, its traffic increased significantly.

Gently the ship coasted in the final yards for docking. On

shore, a gathering of curious Scottish folk watched the

Canadians arrive, and an army pipe and drums band began to play

while people on both the boat and the shore smiled across the

water. The band continued to play merrily as the men disembarked

from the Strathmore, onto Scottish soil. It was The Highland

Light Infantry (City of Glasgow) Regiment, their official sister

regiment; providing their overseas kin with a red carpet

welcome to Great Britain, and of course, the war. Over the time

spent training on the island, the officers of The City of

Glasgow Regiment would go out of their way to establish healthy

relations, Chuck Campbell recalled the gatherings:

"A lot of us didn't drink or smoke... this

surprised a lot of them, I remember one of them said, you call

yourselves highlanders?"

Bare Bones:

The anatomy of a 1941 infantry battalion

Like every Canadian unit to arrive in Britain, the

H.L.I of C was an essentially bare bones organization. They had

stepped off the SS Strathmore with little more than themselves,

some personal equipment, and a .303 Lee Enfield rifle. Before

they could serve in any useful capacity, they had to undergo the

metamorphosis from being a simple gathering of riflemen into a

modern infantry battalion.

Back at Debert Camp, the manoeuvres contained so many notional

factors and equipment that, in hindsight after years of training

in Britain, seemed like children's games: "... on this attack,

there would be mortars suppressing the enemy position ...you'd

have carriers to tow field guns up after consolidation ...

notional tank support... notional artillery support...”

All of the equipment they had been told of was about to become

an organic part of the H.L.I; the latest anti-tank guns, mortars,

heavy machineguns, tracked vehicles, trucks, and jeeps were just

a few of the items which transformed the simple gathering of

riflemen into a formidable fighting machine.

Qualifying courses were taught mainly by the British on how to

use every new item. For weeks or more at a time, soldiers and

officers alike would depart from the HLI’s lodgings to take

special training courses; after which platoons, each of which

were much larger than they would invariably become part of the

new the average rifle platoon of 36 men and each providing a

specific role: "Combat Support Company".

Left:

The H.L.I. of

Canada pipe band, with A. Corstorphine as Pipe major.

In the background one of the bikes used later for

the Normandy invasion.

(Photograph courtesy of H.L.I. veteran

Mr. A.L. Harris.) Right: Pipe Major Art Corstorphine,

relaxing with some H.L.I. of C. officers, in England.

Bognor Regis, Sussex 1942, the Pipes & Drums of the Highland

Light Infantry of Canada, 9th Bde. of the 3rd. Can. Inf. Div.

Billets at Bognor Regis November

1941-May 1942

Once equipped, the first task of the H.L.I. was to

defend the island of Great Britain from invasion. Most British

units by this time were fighting abroad which meant the

Canadians were the backbone of defence against any possible

invasion. They first garrisoned at Camberley on 21 October 1941,

but were only there for a month. On 30 November they moved to

the English south coastal town of Bognor Regis and there they

would stay until May 1942. Here the H.L.I. were able to mingle with

the population, and, even though the enemy occupied coast of

France was visible, they lived as close to being regular

citizens as could be expected.

Many an English family opened their doors to allow these

Canadian men in their homes, their worldly belongings in canvas

bag sagging over their shoulders. A civilized existence in a

home meant a bed with sheets and other luxuries for these

soldiers used to living under canvas or their ground sheets up

to this point, while officers stayed in the local hotel on the

beachfront. Here was the first decent opportunity for the men to

have a life on their time off, when the training was over, the

lads were given a night to their own devices. Of course, this

usually meant straight to the pub, where the small beachfront

establishments would quickly fill with bustling young Canadians.

Scotland 1942, in front of an old castle which served as a

headquarters for commando training. This picture is from the

HLI's first trip to The Highlands.

Left to right are Lieutenants

Bill Roelofson of Kitchener (holding a set of bagpipes),

Chuck Campbell, Gait, Doug Barrie, Waterloo, and Sgt. A.

Houghton.

Pipe Major

Corstorphine walking past the North Nova's Pipe Band at

the inspection of the 3Div. Pipe Bands by General Keller, 1942.

Source:

Youtube Screenshot Canadian Army Newsreel, No. 1

(1942)

Invasion training

begins 2 September,

1943 Cissbury Camp

By late 1943 the H.L.I. were

taking part in large scale amphibious landing exercises,

complete with air and naval support. Once it became obvious

their time was coming, the restlessness was replaced by

professionalism. As the men were issued their new Mark 3

"turtle" helmets, unique from units outside of 3rd Division, the

rumour mill churned:

"We'll be part of the invasion spearhead " officers supposed,

"we'll fight into a bridgehead, then be relieved and sent back

to England because casualties will be heavy. "

As he rolled out of his cot in the morning, Lieutenant Charles

Campbell's tent flap was parted open by a duty corporal, who told

him he must be ready to move to Scotland in one hour's time.

"What do I bring? "

"Take what You'd bring to combat, " the corporal replied before

dropping back the tent flap and briskly moving on to the next

officer's tent.

The following day marked the beginning of the H.L.I.'s second trip

to Scotland, without including their arrival from Canada by ship

to the port of Gourock. Their last visit was over a year

previous and the commando style training they partook in was

easily the toughest they had ever done to date.

Beach assault training

The scenario was always

the same: the H.L.I., as part of the 9th Brigade, would conduct an

amphibious assault on an "enemy held" beach front village. With

the support of air and sea power, the ground troops would

destroy all resistance before taking on a defensive posture in

expectance of an enemy counter-attack. Reinforcements would be

on the way to push the advance inland.

The troops are twenty yards from the beach when their landing

craft stop and the ramps drop. Like ants from a matchbox, they

swarm out and over the beach, quickly taking advantage of any

cover available. There is almost no pause as they, in small

groups, use fire and movement to capture the enemy buildings and

trenches.

Captain Jock Anderson talking to a drummer of the H.L.I. of

Canada's

pipe band, who is holding a rope tension snare drum.

Enter

"Genial" Jock

Bournemouth, 1943

Twenty nine year-old

Captain Jock Anderson was as Scottish as one could be; provided

that Scotsman didn't smoke or drink. He was a kilt wearing,

bagpipe playing, born in Edinburgh man who had in recent

years immigrated to Canada. Jock's life was only just taking off

when the war broke out; not only had he recently graduated from

the University of Toronto, but he was also married and his wife

expecting a first child. Not all educated volunteers shared the

same reasoning or desire to be an officer, Jock was by no means

a military man, as was the case with most volunteers. He fit in

with the vast group of male citizens who thought simply that if

the country was at war, he'd get in the fight and do his bit.

So, with his mind made up that he would enlist, he reported to

the 48°' Highlanders downtown Toronto armoury. However, his

education meant that the recruiters were obligated to make him

something other than an infantry private. They first began paper

work to make him a naval officer, but eventually he ended up as

part of land forces. After completing a basic training course in

England, Captain Jock Anderson was finally attached to an

infantry regiment, and a highland one at that. He introduced to

the officers ... as their new padre.

1944, 3 June

Anticipation again mounted

when they were given notice to move by 2230 hours that evening.

After donning their full battle gear, issue of ammunition,

checking and re-checking their weapons and equipment, they were

told the move was postponed until at least 0400 the next

morning. "Sea stores" were issued in the meantime. These

consisted of one "Bag, Vomit," sea sick pills (which would not

work adequately for most), one "Mae West" (a type of life

preserver) and lastly the handy "Tommy cooker" was received with

favour by the men.

"This is it"

Commanders cleared their throats for the most important set of

orders they had ever given to date: "Good day, men, I know the

past while has been difficult, but I now have our orders; THIS

IS IT." The operation was called Overlord.

Left:

The H.L.I. of C. load onto Landing Craft, Infantry, Large at

Southhampton, 4 June 1944.

Right: Camouflage netting conceals the contents of these

landing craft in Southampton harbour.

4 June

0300 hours

"This is definitely the

real thing" Heavily burdened with equipment, they moved to the

nearby port of Southampton. A rifleman's battle load was

crushing. In addition to weapons and ammunition there were

rations, shovels, picks, personal gear, and even extra rounds

for the two-inch mortars. Magazines for the Bren machmeguns were

spread out amongst all. They also carried bicycles to take

ashore, which would be used to keep up with the mechanized

units.

5 June

The following day arrived

with renewed assurance from the officers that they were going to

invade.

Between 1300 and 1400 hours, the Highland Light Infantry of

Canada's flotilla of four Landing Craft, Infantry, Large and a

special craft for the Bren carriers slipped away from the

harbour quietly with no fanfare with the exception of a few dock

workers waving them off; while one of the pipers played "Road

to the Isles."

Mealtime for infantrymen of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada

(with bikes)

on board a landing craft, en route to France on D-Day.

D Day

6 June, 1944 0400 hours

The inky blackness

shrouding the English Channel erupts with light and thunder as

the invasion fire plan initiates with a massive naval shelling.

Fighter-bombers are on their way by first light and this

combination amounts to a preparatory bombardment the likes of

which history has never before witnessed. From the decks of

their landing craft, officers had a grandstand view of the

fireworks, their confidence boosted by such a display of

firepower.

The H.L.I. of C. at Bernières Sur-Mer, disembarking with their

bicycles

The H.L.I, with 9th.

Brigade, was supposed to land on code name Nan Red beach right

behind the first wave of attackers, but instead were redirected

to Nan White after chugging in circles for hours. White beach

was the town of Bernières- sur-Mer, and on this beach the H.L.I

arrived late in the morning, just after 1100 hours.

The Queen's Own Rifles from Toronto had captured this beach at a

loss of over 100 casualties. As the HLI's craft approached,

bodies of dead Q.O.R.'s bounced and skidded along the hulls, but the

invaders could not pause to pick up the dead. Two sailors of

each landing craft jumped down into the corpse strewn water and

waded to the shore, holding on to separate ropes so that their

craft may be steadied for disembarkation. With that done, the

troops grabbed their bikes off the decks and descended into some

four to five feet of water.

Gathering in Bernières, the H.L.I expected to mount their bicycles

and follow behind a rapid advance of tanks and mounted infantry.

But instead, they spread out and waited while the tanks

attempted to knock out hidden field guns which had already hit

three of their own M-10 self propelled guns. Meanwhile, the

citizens of Bernières were out of their homes, thanking soldiers

with offerings of wine and milk.

It was late in the afternoon when the advance got under way, and

the H.L.I mounted their bikes and headed for Form Up Point Elder,

which was in fact the village of BenySur-Mer, arriving by 1915

hours.

Moving as fast as they dared, all Canadian units pressed towards

their D Day objective, Carpiquet airfield. The North Nova Scotia

Highlanders and tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers led the way for

the 9th "Highland Brigade", clearing out pockets of

resistance and suffering only a few casualties from constant

mortar tire and sniper's bullets.

3. Le Buissance and Bloody Buron

8 June-8 July 1944

Hell's Corners is just down the road After the catastrophic

ambush on D Day plus-one, which saw the North Novas and

Sherbrooke Fusiliers suffer the loss of nearly half their men

and tanks, the 9th Brigade holed up the twin villages of Le

Buissance and Villons le Buissance. The HLI's allotted position

would face the town of Buron, and it became clear that

eventually they would come to terms with the enemy there;

however the more immediate task was to dig in while Pioneer

Platoon was set to work clearing their surroundings of mines.

Padre Jock Anderson received his initiation of combat at Le

Buissance as much as any rifleman. For him, it meant a body

wrapped in a blanket and a standard military burial, after which

the corpse is lowered into a temporary three-foot grave,

adequately marked to facilitate recovery later.

The tragedy of Caen

By 2200 hours, the city of Caen's north end was being

obliterated by Lancaster heavy bombers, killing hundreds of

French citizens and very few German soldiers. The reasons for

doing this would be defended by the Generals for years after,

but it was clear for those who witnessed the aftermath that the

bombing of Caen was nothing short of criminal.

From their slit trenches, any Canadian, British or German

soldier could see the monumental firestorm consuming the ancient

city. Airplanes continued to drop bombs well after Caen was

surely already flattened. The resonant vibrations from these

explosions traveled through the ground and under the feet of

soldiers, as bits of dirt dislodged from the trench walls and

cascaded onto army boots before settling on the earthen floor.

8 July

Morning, just before 0500, every soldier was in a two man slit

trench, waiting for the guns to open up and the order to move to

the assembly area. In these trenches, they squatted down on

their haunches or sat with their knees tucked in on the dirt

floor. It was uncomfortable to stand when loaded down with Bren

magazines, hand grenades, hanging bandoliers and shovels. The

combined weight pulled at the shoulders and dug into the backs

of necks. It was a last chance for a smoke, even though you

weren't supposed to. You could cover up when lighting it, then

share the cigarette with your trench partner, passing it back

and forth without being seen.

On one knee, the rifle sections waited in arrowhead formations;

just as in training. Last minutes were spent adjusting kit, and

talking to the man to the right and left while section

commanders and platoon sergeants made visits to their men,

reassuring them and inspecting gear. Each NCO and officer also

carried a curette of morphine to administer to the wounded, with

the instructions to write "M" on the casualty so that medics did

not mistake the comatose wounded for dead.

"Now boys, we're gonna charge!"

"C" Company's advance was no less harrowing. When the order to

advance was given, Piper Sagan of the pipes and drums band

defiantly stood up at the very front of the company, clutching

not a weapon, but his beloved bagpipes instead. In amazement,

George Mummery of #13 Platoon watched him breath air into his

instrument, which made a droning sound as he did so. But Piper

Sagan never got a chance to play; George: "he took about two

steps before he got it. " (Sagan survived his

wound and the war, and lived more than 50 years after.)

When George's platoon commander, Lieutenant McCormick, ordered

#13 Platoon to advance, they barely started moving before being

forced to the ground by machinegun fire. Pressing as close to

the earth as possible, streams of bullets could be heard buzzing

inches overtop, like a nest of angry hornets. Eager to push

forward, McCormick rose up from the ground and called out to his

platoon, "Now boys, we're gonna charge! "

In disbelief the platoon just watched him as he tried to coerce

his men onto their feet; bullets hit the spade of his shovel

with a pang beside his head, and while he called out, George

Mummery saw him shot through his body and both eyes. After he

dropped backwards, lying dead on the ground, the platoon crawled

the distance to Buron. (After the battle, Padre

Jock said "I knew he'd do something like that. ")

Padre Jock Anderson was still at work. Even when all of the

wounded were evacuated to the advance aid station, he had the

task of collecting the dead. He and his driver, Albert Mitchell

of Galt, used standard issue military grey blankets to wrap the

bodies in, picking them up from the collection of corpses and

carefully preparing them for a standard military burial under

the cover of an apple orchard. Each body was a man Jock had

known, had spoken to, had offered encouragement to when they

confessed their fears.

"Every man has his breaking point, " Jock said, recollecting the

terrible task which haunted him for the rest of his life.

He began to feel annoyance with Mitch, who was a furniture

upholsterer in Galt. It seemed as though he was applying his old

trade as he carefully wrapped each corpse into a neat and proper

package.

"MITCH, can't you work any. faster?" Jock snapped. Without

looking up from his work, Private Albert Mitchell responded to

the padre, "They gave their lives and now this is the least I

can do. "

Jock felt ashamed and fell silent as he worked for the rest of

the time until they ran out of blankets. He drove on his own

back to the rear echelon to get more, but they were also out; so

he drove onwards to 3rd Division's facility. It was there he

became furious with an ignorant store-man:

"The store-man says to me, 'you've had enough blankets already,'

that's when I started to become upset, I was yelling and I broke

down and started to cry. "

The colonel commanding the facility had Jock put under with a

sedative, and hours later he woke up laying on a stretcher,

wrapped in a blanket with a medic's tag attached which read:

"Battle fatigue. Return to England. "

Jock sat up, ripped the tag off, and stood up. Shaking off the

effects of the sedative, he left the aid station and managed to

return to the H.L.I within the hour.

When Lt. Campbell and Major Edwards arrived for orders, it was

approaching 0200 hours. No one had slept for almost 24 hours and

hadn't slept properly for more than that. Geordie Edwards was

both furious and grief stricken. He had been left behind as an

LOB and let his colleagues go without him into a meat grinder

until Smokey Griffiths was wounded, after which Geordie took

command. When Brigadier Cunningham told the assembled officers

that they would not stop before going into Caen, Major Edwards

became outraged, as well were the other battalion commanders.

Chuck Campbell:

"They said, 'we're going into Caen ', and he (Edwards) said,

'With what? We don't have anyone left! "'

No one was the same after Buron. They would forever after belong

to a class of humans separate from the rest of society; those

who would be spared the horror of battle could never be expected

to understand. But the war would not stop for them on this day

to mourn the loss of comrades; not even a brief ceremony to

recognize what had happened on the 8"' of July, 1944 to the

Highland Light Infantry of Canada. No matter how justified the

war was, there could never be glory in it; even when every man

fought so heroically. It was simply a terrible job which had to

be done because there was no other choice.

Sixty two dead and 262 wounded (many of whom would later die),

which left roughly half of them standing. Like the thousands of

other battles that took place in Europe, Buron was the epitome

of war; and when it ended there was nothing but the living

history, told by survivors. As the troops marched on to Caen,

they left behind an orchard filled with rows of rifles stuck

bayonet first into freshly churned earth, crowned with a dead

man's helmet.

With rifles slung they marched down the road like zombies and

eventually one could not look back to see Buron anymore. For the

ragged survivors, it became merely a memory; a window of time

and space to peer into a piece of man made hell which tore an

enormous empty void in the soul.

Private R.O. Potter of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada

repairing his bicycle, France, 20 June 1944.

4. The Cost of Liberation

More than 24 hours of hellish combat had gone by, and sleep was

the only thing any soldier wanted. But instead, after scarcely

having enough time to bury their dead comrades, the H.L.I were

given marching orders; Caen was to be occupied by nightfall.

While reconnaissance units probed forward, the weary H.L.I

formed up by company, filing on both sides of the road. There

was no need to spread out in the fields in arrowhead formation,

the North Novas had bounded past them right after the capture of

Buron, which had made them subject to the same intense shelling

for most of their advance into Franqueville. Snipers, machinegun

posts and mines were hampering advances by the 9th Brigade,

which was led by the S.D.G.'s, who had captured Authie the day

before with considerably light resistance offered.

As they entered what was left of Caen, it became obvious that

the soldiers who fought were not the only ones suffering. Two

nights previous they had heard and seen the bombardment of the

ancient city, it was presumed that at least German army

formations were being targeted. But this was no surgical

operation. Caen was simply carpet bombed, and soon they realized

that virtually no Germans were in the city itself, just innocent

civilians.

Caen was reduced to a heap of smoldering rubble, with the living

French civilians trying to rescue people trapped in collapsed

buildings, pick up the dead, and salvage what they could. With

their homes destroyed, they were now refugees in their own city.

A citizen of Caen described seeing the first allied troops

arrive:

"At 2:30 p.m., at last, the first Canadians reached the Place

Fontette, advancing as skirmishers, hugging the walls, rifles

and Tommy guns at the ready. All Caen was in the streets to

greet them. These are the Canadians, of all the allies the

closest to us ... the joy is great and yet restrained, people

forget the Calvary that we have been undergoing since the sixth

of June. "

"Flowers and good wishes strewn everywhere, " the H.L.I War

Diary states, "these people were really pleased to see us. "

H/Captain John M. Anderson, Chaplain of the Highland Light

Infantry of Canada, talking with Private Lawrence Herbert in his

trench near Caen, France, 15 July 1944.

14-16 July

After marching to the north end of Caen and once again occupying

the grounds of a seminary, the H.L.I was given 48 hours rest, as

was the entire 3rd Division. The Canadian 2nd Division had

landed and now took over the front lines so that the 3rd could

lick its wounds.

Hot showers and a new change of underwear and socks were

gratefully received; the old ones being tossed into one large

hole and burned! Under a brilliant hot sun, they washed the rest

of their clothes, and while these dried on improvised clothes

lines, laid down for precious undisturbed sleep. After a hot

meal the troops were treated to movies under a canvas tent,

courtesy of the Salvation Army, and even an issue of beer and

liquor. Being as it was the first official issue of alcohol, it

meant the troops had not officially dabbled in the local cider,

calvados.

The battle for Caen continues "At 0410 hrs we were in position

at MR (Map reference) 069715. The brigade and supporting arms

lined the west bank of the river ORNE and dug slits in its ant

infested soil. At 0540 our morale was raised by one of the

greatest air assaults of this war 1000 Lancasters

commenced dropping them on VAUCELLE. At 0645 hrs. the medium

bombers started their attack on the enemy gun area. " - War

Diary.

0820 hours

With other units leading the attack, the H LI's crossing of the

Orne River at 0820 hours was uneventful, walking over a double

"Bailey Bridge" dubbed "Winston" and "Churchill" by the British

engineers who constructed it. After crossing, they turned south

towards the industrial sector of Caen known as Faubourge de

Vaucelle. On their left, as they walked, was the impressive

sight of dozens of tattered glider aircraft which marked where

the British 6th Airborne Division had landed the night before D

Day.

The pipe Band playing in battledress after the liberation of

Caen, France 1944

20 July

As they approached the fortress of Boulogne, resistance was

expected at some point, it was just a matter of where and when.

Earlier that day, the North Novas came under machinegun fire

from a road block not far from the HLI.

Leaving the town of Samer gave way to more beautiful French

coastal countryside; to their front, a bank of sand dunes

straddling the road came into view as they advanced.

It is possible they heard it first; a muffled concussion sound,

like a car door being slammed in the distance, thunk. If so,

there may have been a momentary pause before reacting to the

unmistakable sound of an eight centimetre mortar tiring. From

this distance, the flight time could be greater than ten seconds

before the first round hit; but the enemy machineguns would open

up the moment their quarry started to take defensive measures

against an ambush. The bulk of the section was able to take

cover in the ditch on their side of the road, but on the other

side, Cpl. Banks and Major Sim were hit almost immediately.

Both bodies of Major Sim and Cpl. Banks were on the opposite

side of a road raked by fire, there was no chance of extricating

them until the enemy were dealt with.

When Doug Barrie's team had arrived with the trapped section,

but not the two casualties, Padre Jock Anderson decided to mount

a Bren carrier himself, bringing with him a large Red Cross flag

which was prominently displayed as they drove to the scene of

the ambush. Although the Geneva Convention prohibits firing at

the Red Cross, the padre came under fire and had to retreat

empty handed.

Night patrol

That night, The Regiment spread out into an all around defence,

each company using what cover was available; a patch of bush, a

portion of high ground, or sometimes the ditch along the side of

the road would have to do.

Mist Covered Mountains

7 September

Although Major Gord Sim's body was recovered by a patrol, Cpl.

Banks body had to be dropped when hidden enemy began firing on

them.

It was getting late in the day, but an early summer evening

provided enough light for the burial party. From the safety of

the battalion's perimeter they set off with the body of Major

Sim to a church cemetery in a nearby village named Condette.

Captain Jock Anderson had selected this spot from his map, and

in the empty village the jeep parked, after which the funeral

party unloaded the body, which was neatly wrapped in a standard

grey military blanket on a stretcher. Through a typical high old

wall surrounding the church grounds the small procession made

their way; there was Jock, Doug Barrie, a piper and four

soldiers carrying the stretcher as pallbearers.

By the ancient wall a spot was picked to dig, and it was quiet

as they did so, just the sound of shovels churning the earth.

Then, Simmy's body was carefully lowered into the shallow grave

dug to military standards, to facilitated later recovery, and

Jock completed the service. The piper then played a lament which

echoed beyond the church grounds and the empty village, while

the burial party listened in silence. Long shadows of a late

summer day cast over old gravestones, and a newly placed wooden

cross. The tune was called Mist Covered Mountains; it was the

fulfillment of a request Gord had made to Jock:

"...he said, `I'm either going to get the Victoria Cross or I'm

going to die; and I think I'm going to die. So when they bury

me, I'd like them to play Mist Covered Mountains. "'

"I marked it on the map where he was buried, " Jock explained,

"and showed it to the CO ... and he says, `Padre! What are you

doing? We haven't cleared that place yet!"'

It is a depressing affair that the body of Cpl. Banks was left

behind as the HLI moved to new positions in the forests

surrounding Mont Lambert, just outside of Boulogne. The S.D.G.s,

who took over in this area, reported the Free French spotted

Germans in the cover of night booby trapping his body; a common

practice.

3rd. Div. infantry in action. There are less soldiers

wearing the D Day "Turtle” helmets in late war pictures of 3rd.

Division.

The others, wearing regular "Tommy" helmets, are replacements.

General Simonds plans Operation Wellhit; (the

capture of Boulogne)

Canadian Operation Wellhit was dubbed and preparations began in

the beginning of the month of September. Its objective was to

capture of the coastal city of Boulogne using 3rd Division,

after which the allies would use its port immediately, as the

flow of supplies from Normandy was too slow.

By 8 September, Medium bombers were dropping their payloads onto

Boulogne, even though the civilian population was for the most

part still in the area. It was, like the bombing of Caen, not

the precursor to a large scale attack either (although

Montgomery and Eisenhower had wanted the attack to go in by this

date), it was instead all part of another meticulous plan

created by Canadian General Simonds (who was a protege of

Montgomery). These plans were the product of his retreats to his

caravan and chain smoking until a solution was formulated and

orders written. Like the numerous failed attacks in the Normandy

and Falaise region, Simonds was heavily criticized for again

taking too long to send his troops in.

Meanwhile, the HLI had opportunity to rest under the cover of

the Foret de Boulogne. Although they altered their positions

several times to accommodate the massing of 3~d Division, their

stay was comfortable enough. The Salvation Army, (or "Sally

Anne") set up a movie screen and projector in a local school

(formerly used as a German headquarters) for the troop's

pleasure, inside of which many of them had sleeping quarters;

"This place is just like a hotel, " a soldier commented. The

glorious rest went on for over a week, which served opportunity

to write letters, sleep and even 72hour leave passes were

allowed in small numbers, (the leave centre was a hotel complex

on the Normandy coast, several hours drive from the Boulogne

area).

Cap Gris Nez

"We were later warned to be ready to move by 0900 hrs of the

24th to the CAP GRIZ NEZ area, " the War Diary records,

"Preparations were set in motion and the battalion again settled

in for the night. The following day's march in the pouring rain

was described as "extremely miserable " as they arrived and set

about occupying the local area.

Their task here was to capture the huge coastal guns which

existed on Gris Nez (which translates to "Big Nose"), a large

outcropping of land which the Germans built giant guns on to

interdict allied shipping and to harass the port of Dover.

Described later as "skilful and inexpensive" the capture of Cap

Gris Nez was necessary to clear the way for shipping traffic.

The HLI honoured the town of Dover, England, by having the

captured Nazi standard and sword of the Gris Nez battery sent to

them as a gift "... in appreciation of the way they stood up

under four years of shelling from these huge guns. "

Rest and Relaxation

The following few days were invested in rest and relaxation for

the troops. Seventy two-hour leave passed were granted to go to

the leave centre, and trips to the Vimy Ridge memorial took

place. Bill Marshall was greeted back by peers who were curious

to know how the social scene in England's hot spots was:

"England is apparently still the same although there is a

shortage of Canadians according to the London girls.

"The Vimy trip turned out to be a real drunk-fest," Charlie

Bradley wrote, "It was a real blow-out that night. It was pretty

lonely for the truck drivers, going back; most of the outfit was

asleep in the back of the truck. The guys who had to stay behind

must have had a hell of a time unloading the guys. Did we ever

feel bad the next day! "

H.L.I. troops wait for the order to advance somewhere near

Breskens, Holland.

6. The Scheldt and The Waal Flats

The Dutch port of Antwerp was North West Europe's largest, and

had been in allied hands since early September. However, the

entrance to this port was an estuary known as The Scheldt.

Without its capture, Antwerp could not be used.

The estuary's defence consisted of one fortress on Walcheren

Island, and another on the mainland at Breskens. It was the

mainland which would be the concern of 9th Brigade. Peter Dewind;

Dutch Underground hero Thanks to an extremely brave and strong

Dutch Underground fighter named Peter Dewind, the 9th Brigade

received invaluable intelligence which they would exploit to

full advantage.

8 October

Loaded 20 men per Buffalo, the battalion marshalled a column of

some two dozen carriers at an assembly area just east of the

coastal town of Oostakker. From here, under the cover of

darkness, they were to enter the water and float down the

winding Terneuzen Canal, arrive at Terneuzen, then get up on and

cross a small portion of land which would technically be the

start line. From there, dip back into the water, spread out into

assault formations and cross the narrow Channel before hitting

the beach.

All

this was to occur without the Germans knowing.

The Buffalo amphibious carrier was indispensable for the

infantry dealing with the massive flooding across Holland.

A Bren carrier could fit perfectly squeezed into the Buffalo's

hold.

Rest and Relaxation in Ghent 4 November

The War Diary:

"Bn. H.Q, Savan St. Ghent. 4-Nov-44 ... Ghent gave the 3th Div a

great welcome -flowers, fruit, etc. The entire division is

billeted in the city. Great kindness has been shown by the

people of the city. " Four days of glorious rest lay ahead for

the battalion, as well as for all of 3rd Division. Field

Marshall Montgomery arrived and all regiments provided

representatives to receive praise.

Ghent was as close to a holiday as could be expected under the

circumstances. Both the officers and sergeants held separate

dances, accompanied by civilians and nurses. The War Diary:

"Conduct of the troops is excellent... The odd `rear area

warrior' has been straightened out on a few details regarding

life at the front but nothing violent has occurred. It is hard

to credit but each man has a better billet than the other. This

is tribute to the hospitality of GHENT. " But by 9 November, the

R&R was over and it was time to get back to the war. The War

Diary:

"Morale is a notch lower than during our stay in GHENT. It is

hard to be dragged from riches to rags in so short a time. "

"B" Company, H.L. I. of Canada Universal Carrier,

Speldrop, Germany, 24 March 1945. (L-R): Company Sergeant-Major

R.E. Bryant, Private L.J. Mullin and Private T.C. Galbraith.

The Waal Flats November 1944-February 1945

One hundred and twenty five miles from Ghent, the H.L.I

travelled to the Dutch-German border by November 11th, relieving

the American 3rd Battalion of the 505 th. Parachute Infantry.

Through Antwerp's underground tunnel and then through Eindhoven,

the road move by vehicle went smoothly, perhaps even more so for

the H.L.I than with other units since the H.L.I used their

wireless sets, not having been informed, apparently, that the

9th. Brigade was to move under strict radio silence.

On a ridge between Nijmegen and Arnhem they took up positions,

once again in the cold, wet earth. Living quarters were dug into

the ground, like badgers or moles, and torn portions of nylon

fabric (from the derelict gliders of the American airborne)

provided a roof for the dugouts.

Mine tape was strung out between positions, white fabric strands

sagging slightly at waist level between six-foot pickets. These

strands marked gaps where soldiers could safely travel. The

Americans before had laid mines all around without marking the

fields, so engineers had to clear many mines to avoid a

senseless casualty. At night, soldiers on sentry would walk

carefully, one hand tracking along the length of tape as they

went; stepping on an allied mine would be a lousy way to finish

the war.

To their front was a depressing no man's land of shell craters

and water, the derelict gliders interspersed throughout this

landscape, as well as the odd war-torn house or barn.

The months in The Waal Flats were to be a tedious, cold, and

miserable experience. No advances would be made by the Highland

Brigade until the new offensive in February.

Not all of the time was spent in the frozen earth of the exposed

Waal Flats. There were rotations of battalions over weeks to

occupy each other's positions, some of which were more

comfortable than others. One battalion in the 3rd Division at a

time would be held back for rest and retraining, and to serve as

divisional reserve. An institution in Nijmegen served as the

rest area, where movies put on by the Sally Anne and better food

existed. However, much of the Dutch population was starving.

Charles Bradley:

"There wasn't much food for the Dutch people. The kids used to

come around at meal time and beg for food, carrying little pots.

If there was any food left in the cooker, they would get fed. "

First Canadian Regiment to cross the Rhine

The Regiment had moved back to the Reichswald Forest area near

the city of Cleve and was static after the battle for the

Hammerbruck Feature. Troops dug in with the rest of the 3rd

Division, short leave passes were allowed for men to go back to

Nijmegen. The rest in Cleve was enhanced by the presence of the

Salvation Army, who, being ubiquitously equipped with movie

projectors and reels of movies, would set up a tarpaulin tent

(dubbed "The Highland Hut" by its 9th Brigade patrons) while

sporadic incoming artillery fire let everyone present know there

was still fight left in the Germans.

There was a training syllabus to prepare for the next operation,

the crossing of the Rhine; where fanatical resistance was

expected. Range work with the various weapons was conducted, as

well as house clearing drill practiced in the ruins of Cleve

(the city was for the most part demolished). Retraining was

important even for the experienced men, but the green

replacements would need it the most; by this time, soldiers

who had been in the war since D Day were the minority.

As the leadership were issued orders, new maps of the Arnhem and

Wesel areas, as well as various air photos, the allied intent

for the massive assault across the Rhine could be appreciated.

The Americans would cross on the south (right) end, the British

on the north (left), while the Canadian 1St Army had a breakout

role. But the 3rd Canadian Division was lent to the British to

beef up their attack. For the H.L.I, they would go in with the

Scottish 154th Brigade which consisted of 1st and 7th Black

Watch Battalions and 7th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. As

part of the 51St Highland Division, this army of Highlanders

were tasked with establishing a bridgehead on the German side of

the Rhine; the villages of Speldrop and Bienen among the initial

objectives. The H.L.I of C would be the first Canadian unit

across the Rhine.

Speldrop Farm 24 March

At 1730 the H.L.I went in full force; each company taking a

sector of the village.

Officers of the H.L.I. of Canada at the Rhine River crossing,

Speldrop, 24 March 1945.

(L-R): Captain J.A. Ferguson, Lieutenant

E.R. Isnor, Captain D.A. Pearce

Wasp flame carriers moved up and began burning buildings to "A"

Company's front. The night glowed furiously as the tiny village

of Speldrop burned. It began to rain as the battalion was

relieved to pick up its dead and wounded, and the Scottish

carried on the advance. The battle of Speldrop Farm had cost

approximately 13 dead and 23 wounded

War Correspondent Douglas Amaron of the Canadian

Press submitted this article on 28 May:

"The H.L.I. was the first Canadian formation over the river and

the advance party crossed about 90 minutes after the first wave

of Scottish troops. `it was just an ordinary sail, 'said Capt.

Jack Ferguson, of Galt, Ont., support company commander. The

first attack made by the Galt unit was against Speldrop, two

miles north of Rees, where two previous assaults by Scottish

troops were beaten back, Speldrop's widely separated farmhouses

provided the Germans with wide fields of fire and they had the

approaches to the village covered with self-propelled guns. The

Highlanders, who took 65 prisoners in this village, also

relieved two platoons of the Scottish Black Watch, who had been

sheltering in the cellars. "

Bienen

Only hours later, the HLI received instruction to go in the town

of Bienen, where a repeat of the same situation was occurring.

The Argyll battalion had gone in and been counter-attacked in

the same fashion as the Black Watch in Speldrop; this time the

North Nova Scotians came to their aid, but the fighting was so

heavy they could not complete the capture of Bienen, therefore

the H.L.I was tasked to force out the last fanatical defenders.

The evening was spent fighting through this town, and by the

time they had forced out or killed the last of Bienen's

defenders, The Regiment halted at its outskirts and was again

relieved to pick up more of its casualties.

Dutch women (one

wearing national costume)

and child watch of the H.L.I. of Canada's "C" Coy.

passing through Dalfsen, The Netherlands, on 13 April 1945.

The HLI of'C 1940-45 describes the final stages

of the HLI's last battle on 7 April, in the town of Zutphen:

"In many cases the enemy groups would lie low while house

clearing parties passed through or else infiltrated back in the

darkness. In such a manner the battalion command post was cut

off and surrounded by enemy for a time during the night. It was

an uncomfortable situation, for the commanding officer and his

staff as they were not able to make a move without drawing fire

from machine guns and panzerfausts stationed in nearby windows.

However, this situation was rectified when several parties

arrived from the forward companies and the street was again

cleared after some confused fighting. "

After this

fighting, the regiment moved up north to Friesland, to liberate

Leeuwarden and after this they also liberated Harlingen and then moved on to the "Afsluitdijk"

to inspect the fortifications on it and disarm the German

prisoners there, and they also made them clear their own mine fields.

Infantrymen of “B” Company, HLI of Canada, examining a German

“dragon’s teeth” barrier near the Afsluitdijk across the

Zuiderzee, Netherlands, 19 April 1945. (L-R): Lance-Corporal W.J.

King, Privates J.A. Carr and W.G. Scott

April 15, 1945

Leeuwarden,

Leeuwarden, the Capital of Friesland, was liberated by the Third

Canadian Infantry Division. The next day a Civic Reception,

Liberation Parade and Concert on the “Nieuwe Stad” in town was

organized where the combined Pipe Bands of the H.L.I. of Canada

and the North Nova Scotia Highlanders played.

The combined

Pipe bands of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada and The

North Nova Scotia Highlanders arriving at the civic reception

Leeuwarden, Netherlands, 16 April 1945.

... on to the

Concert on the “Nieuwe Stad”

... where some clever countering was to be exercised

They were to return

to Leeuwarden a month later, on May 13, for a Thanksgiving

Service in the “Grote Kerk”.

... on the

Zuiderplein: parade and march through town afterwards.

The Duch civilians always had a great liking for the stirring

sound of the bagpipes, and with the war

over, a good Bar-B-Q was always enjoyed together

as were the sports events. Dutch women (in

regional traditional dress) having tea with personnel of

the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division during the Division’s Sports

Day, Hilversum, Netherlands, 14 June 1945

This is what the H.L.I. of

Canada's collar badges looked like

Cambridge Armoury, Ainslie Street South, Galt, home of The Royal

Highland Fusiliers of Canada. They originated in Berlin, Ontario

on 14 September 1866 as the 29th Waterloo Battalion of Infantry.

It was redesignated the 29th Waterloo Regiment on 8 May 1900,

then the 29th Regiment (Highland Light Infantry of Canada) on 15

April 1915, The Highland Light Infantry of Canada on 29 March

1920 the 2nd (Reserve) Battalion, The Highland Light Infantry of

Canada on 7 November 1940 and then The Highland Light Infantry

of Canada on 1 May 1946. On 1 October 1954, The HLI of C was

amalgamated with The Perth Regiment and renamed The Perth and

Waterloo Regiment (Highland Light Infantry of Canada). On 1

April 1957, the two regiments ceased to be amalgamated and

resumed their former designations. On 26 February 1965, it was

amalgamated with The Scots Fusiliers of Canada and redesignated

as The Highland Fusiliers of Canada'. The Regiment assumed the

appellation "Royal" to become The Royal Highland Fusiliers of

Canada on 7 July 1998.

This is a photograph of the Journal of Captain George Pollard,

as written

during his time in the H.L.I. of Canada.

This photograph and the following photographs, are used by

courtesy of

John Smith (a grandson of George Pollard) who created the page

http://georgepollard.ca/

with the intention of preserving and sharing Captain Pollard's

first-hand experiences from WWII, as written down day by day in

his own journal, which can be found on that webpage, together

with many interesting photographs taken during his time in the

H.L.I. of Canada.

Captain Pollard rose, by a number of trainings, from soldier to

Captain and Padre, and so finally became a colleague of Captain

and Padre Anderson of the H.L.I. of Canada.

This is a photograph

of

Mel

Quick and Sylvia Trickey on the Bognor Regis Baptist Church

steps, after their wedding on November 25th, 1942.

George Pollard en

route in Holland, 1945

George Pollard in

front of the Officers' Mess somewhere in Holland, 1945

Welcome Home on

return at home in Canada, 1945